As I’ve said before, many atheists spend far too much of their reading time confirming their atheism. My attitude is: If your freedom from faith is so shaky that you’ve got to pore over every godless screed available through Amazon, you’re probably still a believer deep down.

Assuming, though, that you’re really interested in expanding your mind (instead of just sponging up a few facts to use in your next losing debate with a theist), you might want to pick up a decent novel. A well-written piece of literature forces the skilled reader to see the world through others’ eyes: those of the characters and, ultimately, the author.

What better way to find oneself in a different time and a different place and a different mindset than to pick up a historical novel? Unfortunately, the majority of books published in that genre are drivel. Far too often, the writers of so-called historical novels do some cursory research and then chug out predictable potboilers peopled by wooden characters that display feelings and motivations reflecting the stupidest modern-day sensibilities. The dialogue in those books is a weird combination of modern English usage, even slang, and a few old-fashioned words ludicrously sprinkled in, usually inappropriately, for colo(u)r. Long paragraphs are devoted to “period” details about clothing, food, architecture, transportation, you-name-it — encyclopedia articles that add nothing except tediousness. Picking up such a book is like being around an annoyingly precocious child determined to tell you what he or she has learned in class today. But by far the worst thing about those third-rate novels is that they almost always include a bogus romance as the main event, as if the only thing a reader could conceivably care about history is whether some bland boy and some drab girl succeeded in hooking up. Yuck.

Because I’m a lover of both history and literature, when I do come across a historical novel that I like, I tend to get excited about it. And I can’t resist sharing my enthusiasm. Right now, I’m working my way through two — two! — historical series, both of which I’m happy to preach about (although I promise not to ring your doorbell at seven in the morning).

The first series is Gore Vidal’s Narratives of Empire, a seven-novel jaunt through American political machinations, starting in revolutionary times and ending in the 1950’s (although a very short section of the final book takes place in the year 2000).

It’s an oversimplification to say that Vidal sees the long story of the United States as a continuous chain of contests between various Machiavellians vying for power. The writing is far too rich to reduce it to a mere hook for a theme. Still, the author does deconstruct our nation’s history, cutting ruthlessly through its sacred bull. The real characters who march in and out of these books are not the same figures you learned about in high school. Oh, they have the same names, all right, but Vidal brings them to life, sometimes shockingly so, often through hilarious dialogue. Over and over again, he records ironic interchanges between people you thought you “knew.” Whenever a real person is involved in a conversation, very little is “made up;” Vidal quotes actual words written or said by the individual taking part. Even those personages for whom Vidal seems to have great respect — Lincoln is a good example — are demythologized.

I can’t quite figure out how the author manages to suck the reader in, but I found myself turning pages eagerly to find the answers to questions like: Will Aaron Burr be found guilty of treason? Is Lincoln going to be assassinated? Who the hell will win the 1876 presidential election? Yeah, I already knew what was going to happen, but Vidal transmutes foregone conclusions into page-turners loaded with intellectual suspense. That’s great writing.

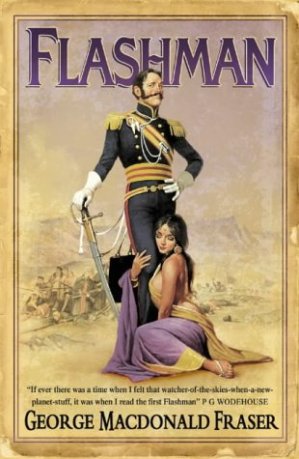

The second historical series I’m making a pitch for here are the Flashman books, all twelve of them, written by George MacDonald Fraser. These were originally brought to my attention by Postman, who delivered the good news in this comment.

Flashman began his literary life as a bullying character in Tom Brown’s School Days, a preachy 19th-century novel for boys, teaching them how to grow up to be fine upstanding Victorian men. Fraser takes the book’s most interesting character, who was likely not to grow up to be a model English gentleman, and examines his life. The adult Flashman is a coward (he calls himself a “poltroon”), a womanizer, a liar, cheat, racist, sexist, and xenophobe. But somehow, he becomes an unlikely star in just about every war fought by the English-speaking peoples of his time.

The conceit of the novels is that Flashman, looking back from old age, has chronicled his life in “packets,” sheaves of remembrances that relate self-contained episodes. The main character screws his way around the world, showing up to play reluctant “hero” in such places as Afghanistan, India, North America, China, the Crimea, and Madagascar, to name just a few venues in which he appears. Fraser, the “editor” of Flashman’s memoirs, helpfully supplies footnotes, appendices, glossaries, and maps.

The series was begun in 1969, near the tail end of James Bond’s original burst of popularity. So it’s possible to read the novels as tongue-in-cheek adventure tales, a la Ian Fleming. Or you could read them as satirical send-ups of military reminiscences. Certainly, each book contains a few history lessons, although you’d have to be a very serious dullard, indeed, if you opened these volumes merely to learn something.

MacDonald’s skill is in creating a believably unbelievable character who, by all rights, should be hateful to nearly every reader. The fact that we find ourselves rooting for him again and again must be related to our human DNA: we’re genetically programmed to be fascinated by hedonistic scoundrels. (Think of all those real-life lying, cheating bastards who keep us spinning through the news cycle.)

As Vidal does, MacDonald manages to un-deify some of the demigods of the past. He also introduces us to real characters whose actual words and actions seem too far-fetched for fiction. (MacDonald uses many of his notes to tauntingly tell the reader “Yep, that’s true. Gotcha!”)

Both series of novels contain plenty of treasures for cynics. The authors tell us, again and again in dozens of ways, not to take for granted anything that we’ve “learned.” Yes, both Vidal and MacDonald seem to say, textbook history may well be written by the victors. But there are always a few skeptics who joyfully refuse to get taken in by the propagandistic claptrap. Nothing in this world should be accepted unquestioningly, should be so sanctified that it can’t be reflected in a satirist’s funny mirror.

Remember: freethinking is not limited only to the subject of theology.

|

Narratives of Empire

Burr

Lincoln

1876

Empire

Hollywood

Washington, D.C.

The Golden Age |

|

The Flashman Series

Flashman

Royal Flash

Flash for Freedom!

Flashman at the Charge

Flashman in the Great Game

Flashman’s Lady

Flashman and the Redskins

Flashman and the Dragon

Flashman and the Mountain of Light

Flashman and the Angel of the Lord

Flashman and the Tiger

Flashman on the March |